Exterior: Chancel East & South Walls

Chancel, east wall

This wall is rubble-built with a few flint patches, the stone being almost entirely local malmstone, with Caen stone quoins and lancet surrounds. A very few dressed stones have been inserted randomly. These are Caen stone blocks, presumably salvaged from previous work on the building.

Chancel east wall

The central lancet is quite a bit higher and wider than the side ones. But there’s nothing visible to indicate that the central lancet had been made larger at any time, so it looks like the windows were originally constructed like this.

Note the narrow horizontal course of flat stones just below the gable on the next photograph.

Chancel east wall, gable

This reflects the building technique: they provide a level base upon which the gable was built.

The buttresses appear to have been added much later than the original walls. The archdeacon’s visitation at the end of the 18th century records that the south-eastern wall of the chancel was collapsing. During the ‘reparations’ of 1864, there was an accidental breakthrough into a vault at that end of the church. Hence the addition of buttresses in 1864.

The buttresses are of Quarr stone, topped with Horsham stone. Quarr stone comes from the Isle of Wight and was widely used for medieval churches in the Chichester area. It was little used after about 1120, when it is probable that the quarries were worked out. The buttresses were constructed in 1864, so probably recycled Quarr stone was used. (There is also a buttress at the north west end of the nave wall, and the tower is also buttressed. In fact despite having been built on rock, the church has suffered instability over the centuries.)

To the right of the four 18th century memorial tablets (see image above) it look as if there could have been a fifth — but there never was.

There are rust stains below the rightmost lancet, and also rust stains underneath the tablets themselves. These stains have come from the window ironwork and from the fixings attaching the tablets to the wall. Rust inhibits the growth of algae on the stones, so emphasising the stains.

Chancel, south wall

It is interesting to compare the north and south walls of the earlier chancel, and photographs of the two walls are displayed adjacent to each other here.

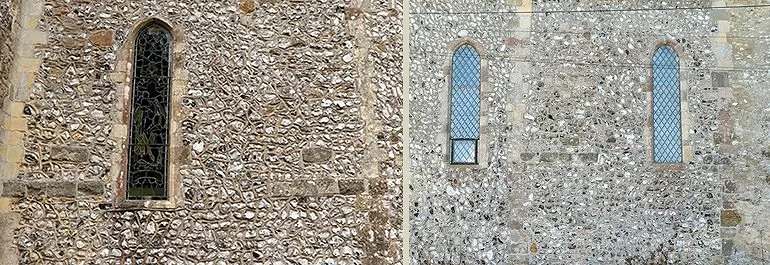

Chancel walls: comparison of south (left) and north (right)

Exactly like the north wall, the south wall shows the clear evidence of the chancel having been extended. Both walls have the vertical course of ashlars about half way along. Both have the short horizontal string of ashlars in the earlier part of the wall, in line with the foot of the lancets.

Both walls are largely flint, with the vertical course on the south wall being a mix of Pulborough stone from the ground up with Caen stone above, the lancets surrounds largely of Caen stone. Like the north wall, the flint varies significantly over the wall. In the early, west, part of the chancel, the flint below the lancet is all laid in courses, which extend higher to the left of the vertical ashlar course. Round the lancet, the flints tend to be bigger and more randomly laid. You get a pretty good idea of how much of the wall must have been re-built after the insertion of the west lancet.

On the north side, the flints above the lancet head are smallish and laid in courses – just like the lower flints on the south wall. It’s tempting to think that the north wall was finished first , with these small flint courses at the top, and then the south wall started, using the same type of flints. It’s difficult to see any other explanation for the appearance of the flint work.

The courses of horizontal ashlars at the level of the foot of the lancets are almost identical on the two walls. West of the vertical line of ashlars at the end of the original chancel there are four Pulborough stone ashlars in each case. This would seem to imply that there were formerly identical windows in both walls, prior to the lancets being inserted. Rather oddly, and maybe this is just a workman’s fancy, in each case there’s a single ashlar a little above the horizontal row, and about the same distance from the former end of the chancel. It is certainly not obvious what constructional reason there could have been for that. A coincidence?

The hard pointing to the flintwork of the chancel is from 1864, to protect the walls after the render was removed by the Victorians.