Exterior: Tower

The tower construction uses a mix of rubble – largely local, Amberley Blue, malmstone, with substantial areas of flint. There are distinct differences in construction from the bottom to the top, with the top quarter largely rubble.

Tower, south elevation

There are two buttresses. The massive one on the left corner, of Pulborough stone ashlars with flint infill, extends about three-quarters of the way up. The buttress on the right, in the corner return with the south aisle wall, is of Pulborough stone and Caen stone blocks. Oddly, the right buttress is not keyed into the tower or the church wall. We don’t know why this is, for even though this indicates that the buttress was built later than the wall, it would have made sense to have keyed it in at least partially. But this would have increased the cost, so we have to assume that money was tight at the time.

About two-thirds of the way up there is an arch, below which the wall is mostly flint, with mainly rubble above. There’s nothing to indicate that the original tower stopped just above the arch, so it would appear to be a ‘relieving’ arch, there to provide additional strength. You would expect that there might be a matching arch on the north side too, which there is indeed.

The flint work below the arch and above the vestry window has very recently been repointed using lime mortar. This flintwork had previously been repointed using cement mortar, which was a big mistake. Cement mortar has two important disadvantages – though these were not recognised at the time. Firstly, it is impervious to moisture and does not allow walls to ‘breathe’. Water gets into the tower through cracks, and will remain inside the walls. The walls are filled with rubble, with numerous cavities, and it is inevitable that water will get inside and cause dampness. Secondly, cement mortar is typically harder than the building stones, so that in freezing weather the stone may fracture – and this was happening here.

In fact every church tower is damp, and while you cannot eliminate it, you can manage it. At Amberley church, the dampness was so serious that in 2018 work was undertaken to rectify considerable damage and to improve the way moisture ingress into the tower was managed. These works cost over £200,000, which was raised by the community, with a major contribution from the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Note the openings in the tower façade: an Early English window at ground level for the vestry. Below the relieving arch, to the left, is a small rectangular opening. It’s quite small for a window, and offset to one side. What was it for? Was it there originally? We don’t know. This opening is into the ringing chamber, so may have been created when the bells were installed, in 1742, to provide light and (maybe) ventilation. It was closed up for reasons unknown, which did not help with the damp problem in the tower, since it reduced the ventilation, and was re-opened in 2018.

Much further up is a long lancet opening with louvres. The latter look modern, which they are, but the surround looks Early English. This may have been an original window, which would make a convenient opening for a bell chamber.

It is clear, from looking at the tower overall, that the building campaign must have lasted around 50 years – perhaps they were short of money. The tower was started in the mid-13th century, but the bell openings and the upper portion of the tower probably date from the 14th century.

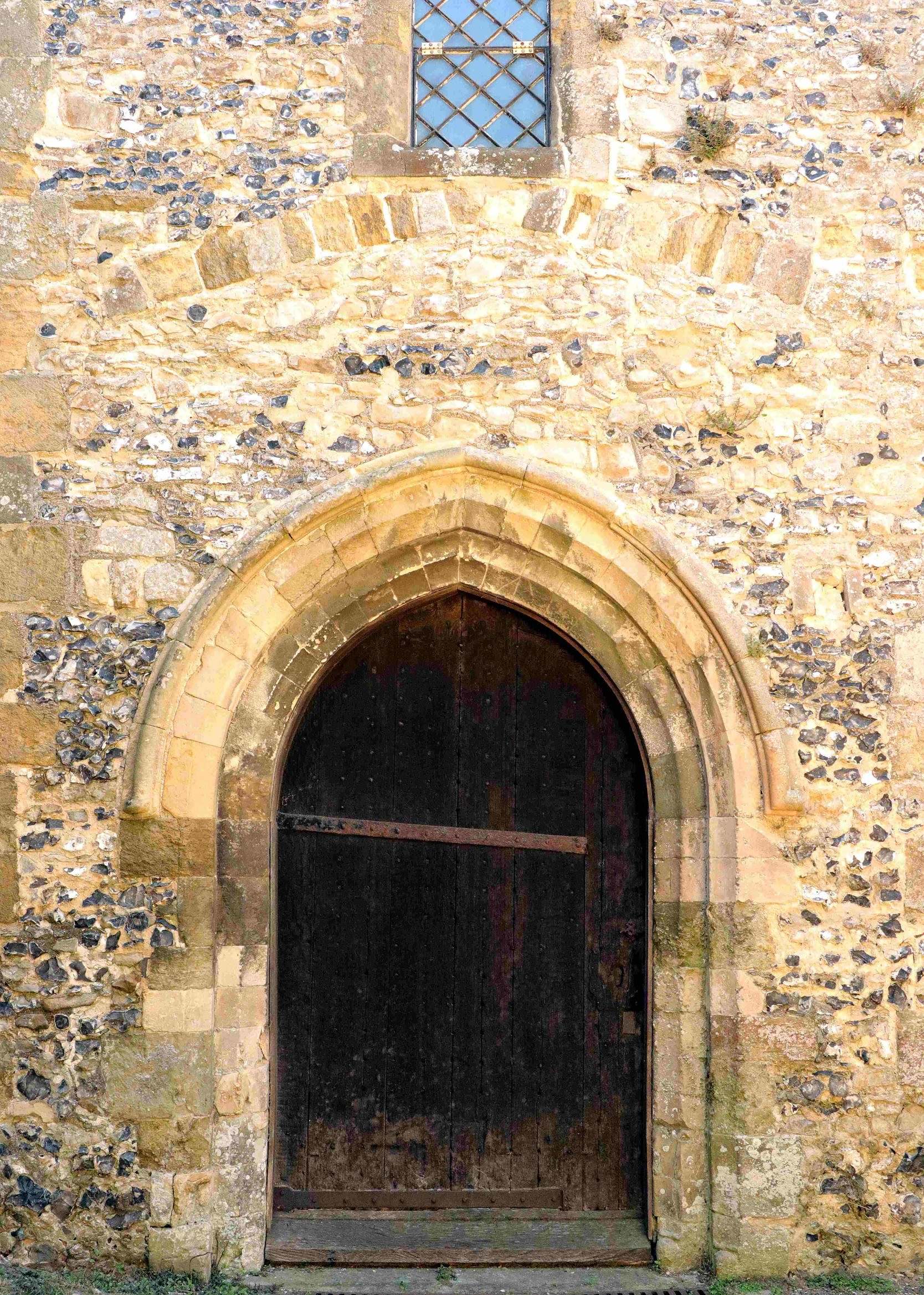

West Door

The west door is quite impressive, much bigger than the original north door, or the now main, south, door.

No caption

Why so big? Remember: the Bishop of Chichester’s summer residence, Amberley Castle, was next door to the church. Immediately opposite the west door is a door in the Castle wall with a sign saying “St Richard’s Gate” – St Richard being the bishop between 1244 and 1253. This gate allowed the bishop direct and easy access to the church from his residence.

St Richard’s Gate

The scale of the west doorway, which is 2.33m (7 ft 8 in) high and correspondingly wide seems to imply that it was for ceremonial processions to enter, with banners flying. A high door would avoid the need for the bishop to doff his mitre or lower his head on entering, or for banners to be drooped. Unsurprisingly, the internal door from the vestry to the nave is almost exactly the same height. The style of the doorway is Early English, like the other windows in the tower, so helping date the tower to the 13th century. In fact the lower portion of the tower was built around 1230, at the same time as the chancel was extended.

The present wooden door, which is of double-plank construction, appears to have replaced an earlier double door, the hinge pintles for which are visible inside the vestry.

Look above the west door. There’s a relieving arch there too, just above the doorway. This arch would have been created to provide additional strength above the doorway to support the upper part of the west tower wall. The Early English lancet window immediately above this arch now provides light into the ringing chamber in the tower.

Notice the sockets to top right and left of the doorway arch. These are putlog holes, used to secure scaffolding during the construction of the tower. The flat stones at the sides and top eased the withdrawal of the putlogs. Surprisingly, these seem to be the only putlog holes now visible in the exterior walls of the church, though there are several in the interior walls of the tower.

Putlog hole above west doorway