Guides to Amberley Church

Glossary

This glossary accompanies the Guides to Amberley Church and contains only terms relating to or relevant to Amberley Church. The explanation of some terms may sometimes appear incomplete in respect of other churches. For example, in the explanation of styles, we do not consider vaults, for there are none at Amberley. For more comprehensive information, refer to the publications listed in the Bibliography.

All illustrations are from Amberley Church.

a

abacus

Flat slab on top of a capital. Similar to an impost, in a classical context the abacus is the upper part of a capital that the entablature rests on.

altar

Originally a stone table or block containing relics, consecrated for the celebration of the Eucharist. Nowadays most altars are wooden tables.

Anglo-Norman

See styles.

ashlar

Squared blocks of masonry cut to an even face, as opposed to unworked stone or rubble. At St Michael’s, ashlars are used for quoins, doorway and window surrounds, courses beneath windows. Recycled ashlars appear randomly in the walls. The photograph shows ashlars, of different types of stone, used to fill in the original north doorway of St Michael’s.

ashlar piece

A vertical timber near the end of a rafter. An ashlar piece forms a triangle with a sole piece, which is fixed to the lower end of the rafter. All the rafters at St Michael’s end in ashlar pieces and sole pieces. In the case of the nave, the sole pieces extend outside of the church forming the wide soffit.

aumbry

A small cupboard or recess for sacred vessels, found in the north wall of the chancel. Most aumbry doors, as at St Michael’s, have disappeared. The St Michael’s aumbry now contains a box with a front cloth cover.

b

base

The moulded foot of a column, half-column, pier or pilaster, usually resting on a plinth.

beakhead

Norman ornament in the form of a bird’s head, or a human or beast’s head, often superimposed as a repeated form on the roll moulding of a doorway arch, but occasionally also on windows and chancel arches and, as a single motif, on corbels. At Amberley, a single beakhead (illustrated) is carved on the chancel side of the chancel arch, but stylised beakheads are also carved on the columns with flat leaf capital.

beakhead, stylised

The columns below, from the chancel arch (left image) and the north nave windows at St Michaels’s (the two images on the right), show stylised beakheads between flat leaves. These capitals show how masons experimented with the carving of capitals in the mid-12th century, adapting beakheads in an abstract way and incorporating them into Classical-based capitals.

belfry

The tower or bell chamber of a tower where bells are hung, also known as the bell chamber.

blind arch

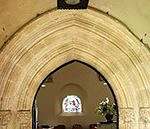

An arch with no opening. The blind arch illustrated appears above the main door of St Michael’s. Why it is present is unknown.

branch-work

Painting resembling branches and foliage. The example from St Michael’s may require a little imagination.

c

capital

Carved top of a column, supporting an arch. It often provides the visual transition between a round column or shaft below and an impost block above, which in turn supports the springers of the arch. See also flat leaf capital, volute.

catslide roof

A catslide roof continues down below the main eaves height, allowing the building to be wider without increasing the ridge height.

chancel

The east end of a church containing the altar, usually reserved for the use of the clergy and choir.

chantry

A chantry is an altar, chapel or separate building dedicated to the memory of a person, family or fraternity, a group of local inhabitants or tradesmen. Donors would endow the chantry, with lands, property and other assets. The income from these maintained the chantry priest, who said masses for the souls of the commemorated. These were abolished in the reign of Edward VI and their funds sequestered by the crown.

chevron ornament

A form of three-dimensional architectural ornament consisting of zigzags formed by mouldings.

claw chisel

A claw-chisel with a serrated edge used for finishing ashlar surfaces. Introduced in the second half of the 12th century, it leaves distinctive parallel tooling marks, usually diagonally, as on this Caen stone ashlar in the north doorway of St Michael’s.

collar, collar beam

Horizontal beam connecting rafters. See collar purlin.

collar purlin

Longitudinal timber supported on crown post across which collars lie. The photograph shows the crown post above the tie beam, the collar purlin (1 o’clock to 7 o’clock) supporting the collars, which stretch between the pairs of rafters.

column

An upright structural member of round or polygonal section, consisting of a base, shaft and a capital. See also engaged column and pier.

consecration cross

In mediaeval times three consecration crosses were usually painted on carved on each of the inside and outside walls of a church – twenty-four in total. They were placed above head height to avoid people brushing against them accidentally. Each cross was consecrated with oil by the bishop. Two crosses are visible on the nave walls of St Michael’s; two others were obliterated in 1864.

corbel

A corbel is a projecting block of stone or timber to support a feature above. A row of corbels, often carved, supporting a parapet, stringcourse or the eaves of a roof is called a corbel table and often is a feature of Norman buildings. It is not known what the corbels at the side of the north door of St Michael’s (as illustrated) supported, possibly a hanging porch.

coursed masonry

Layers of the same type of building material – eg stone, bricks, flints of equal thickness – running horizontally in a wall. Brick-built walls are fully coursed.

Vertical lines of ashlars, especially if runnng the full height of a wall, are likely to be the former quoins of an earlier wall which has been extended. There are several such vertical lines in the north and south walls of St Michael’s. The photograph shows an – interrupted – horizontal course, formerly at the sill level of the original Norman windows, and a vertical line of ashlars which had previously been the corner quoins of the east end of the chancel before it was extended.

coursed rubble

Layers of irregular stones or flints laid in courses. The photograph shows flints laid more-or-less in courses in the nave gable of St Michael’s.

crown post

The crown post is the central vertical post above the horizontal tie beam in a “crown post” roof, as at St Michael’s. The tie beam for the nave roof can just be seem at the bottom left of the photograph. The upper horizontal beams connecting the rafters are called “collars”.

d

double-plank construction

Double-plank construction is one of the earliest mediaeval methods for making door. Simply and robust, double-plan doors are made by joining together two layers of planks – vertical boards on one face and horizontal (occasionally diagonal) on the other. Since it sheds water more efficiently, the vertical face is set to the outside for external doors, as is the case with the west door of St Michael’s.

The earliest doors usually had two or three vertical planks but that at Amberley has six. In some cases the planks were joined together originally with wooden pegs but in most surviving doors these were replaced later with iron nails. It looks like the nails in the St Michael’s door are original, with the protruding sharp ends bent over to provide additional strength. The age of the St Michael’s door is unknown, but possibly 16th century or earlier.

e

Early English

See styles.

eaves

The overhanging edge of a roof.

engaged column

Also referred to as attached, an engaged column is partially embedded in a wall The chancel arch columns at St Michael’s are engaged columns.

f

flat leaf capital

This has a broad, flat leaf at each corner, the pointed tip below the angle of the abacus. The capital illustrated here also has stylised beakheads carved between the leaves.

i

impost

Horizontal projection immediately below the springing of an arch, sometimes immediately above the capital sometimes used instead of a capital. Not to be confused with an abacus. The commonest 12th century forms are chamfered, and hollow-chamfered. Either the upright face or the chamfer may be decorated, and there may be a quirk or an angle roll between face and chamfer.

l

label

A projecting moulding above an arch or a lintel to deflect water. Also called a hoodmould or a dripstone. Only one of the arches at St Michael’s has a label. Bizarrely, that is the internal blind arch above the main door into the church.

lancet

A lancet window is a tall, narrow window with a pointed arch at its top. There are many examples at St Michael’s.

m

mass dial

A sundial used for indicating the times of masses. The one at St Michael’s is missing its gnomon.

mullion

A vertical or horizontal dividing element between units of a window. It can provide a rigid support to the glazing and structural support to an arch or lintel above the window opening.

p

pediment

A low pitched gable above doors, windows, etc.

pier

A column supporting a load. In a church, piers or columns are mostly used to support an arcade, as here at St Michael’s.

pintle

A pin or bolt, usually vertical, on which another part turns. The gudgeon of a hinge fits over a pintle. The, now unused, pintle shown here was used for an older, double, west door to St Michael’s tower. An identical pair of pintles on the other wall of the doorway are used for the current door.

piscina

A basin (free-standing or set in the wall) near the altar, usually on the south side, with a drain leading to consecrated ground in the churchyard. It was used for washing vessels used in the Eucharist. St Michael’s has two piscinae: that pictured here, to the right of the main altar, and one to the right of the aisle altar.

plinth

The projecting block beneath the base of a column, or projecting courses at the foot of a wall; the upper edge is usually chamfered or moulded.

pointed arch

An arch composed of segmental arcs struck from two or more centres. The two segments lean against one another and meet at a point.

principal rafter

See rafter.

purlin

Longitudinal roof timber supporting rafters, usually set in the plane of the roof; framed into the principal rafters, and/or set into a masonry gable. St Michael’s has what’s known as a common rafter roof, without principal rafters or purlins.

putlog hole

Putlogs were pieces of squared timber used as supports for scaffolding during building. A putlog hole generally has a piece of flat stone at the top and one at each side, to allow the putlogs to be extracted easily. The one shown here is above the west door of St Michael’s.

r

rafter

“Common” rafters are uniform inclined timbers supporting a roof. “Principal” rafters are heavier than common rafters and support longitudinal purlins which in turn support the common rafters. The roof of the south aisle at St Michael’s has principal and common rafters, and purlins.

relieving arch

An arch incorporated in a wall to redistribute some of the superimposed weight. The one in the photograph is above the west door (tower door) of St Michael’s. The tower has further relieving arches on both north and south walls.

rere arch

The arch on the inside of a doorway or window.

respond

A half pier or half column, bonded into a wall and supporting one end of an arch or arcade

roll moulding

A convex moulding of a semi-circular section. When applied to the soffit of an arch, it is called soffit roll, if to the face of an arch, it is called a roll.

Romanesque

See styles.

Rood, Rood screen

The image of Christ on the Cross. In mediaeval times, the chancel was reserved for the priest and the nave for the congregation. There would be a screen between the nave and the chancel, with a locked door. Over the screen would be a Rood beam, on which would be fixed a Rood, flanked by the figures of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John. While St Michael’s no longer has a Rood screen, it would certainly have had one, and many churches still do.

Rood loft, Rood stair

A narrow gallery allowing access to the Rood on the upper section of a Rood screen. It is reached by the Rood stair. Most were built in the later medieval period.

round arch

An arch in the form of a semicircle, as are Norman arches.

rubble

The general term for stones of irregular sizes and shapes.

rubble wall

A wall of rubble. The stones may be laid in various ways to give a more regular appearance to the wall or may be laid randomly, as is the case with most of the rubble walls of St Michael’s. The thick walls of mediaeval buildings like St Michael’s church are typically built with internal and external walls more or less separate, with loose rubble in between.

s

sanctuary

The area immediately around the main altar of a church.

Saxon, Anglo-Saxon

See styles.

sedilia

Seats for three clergy, on the south side of the chancel.

shaft-ring

A ring around a circular pier or shaft.

soffit

The underside of an arch or lintel, but more generally, the underside of any construction element, including the material connecting an exterior wall to the edge of the roof under the eaves. The photograph shows the exceptionally wide soffit above the north wall of the nave of St Michael’s.

sole piece

The horizontal timber resting on the top of a wall and connecting an ashlar piece and the lower end of a rafter. The photograph shows the sole piece and rafter projecting well beyond the nave wall at St Michael’s.

splay

Angled reveal, a chamfered surface cut into the walls. The term usually refers to the widening of doorways, windows or other wall openings so that the internal opening is much wider than the outer opening. This increases the amount of light which can enter from windows.

springer

The first stone of an arch or vaulting rib above the springing point. In the photograph, the springers are the voussoirs which rest on the imposts.

springing point

The level at which an arch or vault rises from its supports, ie immediately underneath a springer.

spur ornament

An ornament seen on pier bases, running from the moulding of the base onto the angle of the square plinth. It is sometimes carved with foliage, animal or human heads, etc. The spur ornaments on the arcade piers at St Michael’s are now severely worn.

squint

An opening at the side of a chancel arch to allow people in the aisles a view of the sanctuary The squint was used by the priest at the side altar to synchronise his raising of the Host with the priest in the chancel.

stoup

Holy water basin at the entrance to a church, usually on a pillar or set in a niche.

string course

An horizontal course projecting from a wall, often moulded and at times richly carved. A string course of semi-circular cross-section goes all the way round the chancel at St Michael’s, at a higher level behind the altar, and continuing in the aisle round and under the aisle piscina.

string moulding

Semi-circular cross-section moulding of a string course.

styles

Mediaeval church architecture developed in broad phases or styles, each with recognisable characteristics, primarily in respect of details and decorations. The dating of these stylistic periods is not precise: a style may be continued after a newer style has been introduced, but the shapes of mouldings, carved patterns and foliage, window tracery have evolved consistently.

- Anglo-Saxon: 7th to late 11th centuries. Arches mostly tall and narrow; some triangular-headed arches; irregular segments of stone used in semi-circular arches; arrangements of straight, unmoulded pieces of stone into simple patterns on walls (“pilaster strips”); decorative sculpture often looks primitive.

- Norman or Anglo-Norman: c.1070 to c.1170-80, or “Romanesque”, brought to Britain at the Norman Conquest. In the 12th century, large numbers of churches were built or rebuilt. During the late 11th century there is an overlap of Anglo-Saxon and Norman features. Semi-circular arches are characteristically Norman: by the early 13th century they no longer appear. Windows in the early part of this period tend to be short – usually less than a metre or so high, though St Michael’s is exceptional, with the west window of the nave being more than two metres high and the north windows there over one and a half metres high. Windows of this height indicate the 12th century. Mouldings provide good clues to Norman period architecture. The attached shaft, a narrow semi-circular column apparently stuck to a wall, is characteristic. These appear at the side of each of the round-arched windows at St Michael’s, and frame the chancel arch. The volute and flat leaf capitals on the St Michael’s columns are again characteristically Norman, as is the chevron pattern on the chancel arch. The beakhead is a further 12th century motif. The presence of an apse is an almost certain indication of a Norman church; there is some evidence that St Michael’s originally had an apse.

- Transitional or Early Gothic: c.1160 to c.1190-1200. This is evolutionary phase rather than a style. Pointed arches began to appear. The carvings on capitals become more detailed. Chevrons have gone by 1220, replaced by new, more intricate motifs. Thousands of churches had their east ends rebuilt from the late 12th century onwards, almost all involving the replacement of an apse by a squared end. This increased the space round the altar, and allowed the east wall to accommodate a large ornamental arrangement of windows. St Michael’s is quite typical, the early part of the chancel, dating from 1140, had a squared end, which most likely replaced an apse. The lengthened chancel has three large windows at the east end. So the development of St Michael’s straddles the transitional period.

- Early English: c.1190-1200 to c.1260. The lancet arch is a good, though not foolproof, indicator of Early English period. These were most common between the late 12th and mid to late 13th centuries. Windows, mostly lancet, became important parts of church design. Early English lancets have no additional detailing. Stepped lancet arrangements of three or more windows as at the east end of St Michael’s) are common.

- Decorated: c.1260 to c.1350-60. In this period distinctions between wall and window, building and fittings, become a little blurred. Much more, and more complex, detailing appears. Tracery appears within windows. Although simple tracery had been introduced around 1240 in England, tracery became more complex through the decorated period. What little tracery there is at St Michael’s appears in the 20th century south-window of the aisle. Decorated foliage becomes quite complex and crinkly, as in the south doorways capitals at St Michael’s (of c.1300).

- Perpendicular: c.1330-50 to 16th century. The design elements become unified: here is much less variety in these than previously. The panel became a primary motif: a shallow rectangle headed by a cusped (ogee) arch. The panel could be carved over walls and windows alike. The architecture of St Michael’s essentially stops short of the Perpendicular period, only the rectangular exterior surround of the aisle’s south-west window showing Perpendicular design origins – though repaired in the 19th century.

t

tabard

A short garment, sometimes of silk, worn over armour to display the wearer’s coat of arms so that he could be recognised in battle, replacing the longer surcoat. The Wantele brass (of 1424) in St Michael’s is the earliest surviving example of an effigy with an emblazoned tabard over the armour. Heralds of arms still wear tabards at state occasions.

tie beam

A transverse timber, usually of heavy section, connecting two walls. When framed securely into roof timbers it removes the problem of lateral thrust. The photograph of the nave roof timbers at St Michael’s show the vertical crown post above the tie beam, the horizontal collar beams between the rafters, forming the trusses. The collars are all fixed to the longitudinal collar purlin.

The vertical timbers at the ends of the rafters are ashlar pieces.

tool marks

The traces of an axe, chisel, drill etc. preserved on the stone. Many of the dressed stones at St Michael’s, inside and outside, carry tool marks.

tracery

The use of relatively fine stonework within window openings to create new types of window. The tracery shown here (south-west aisle window of St Michael’s) is of early 13th century design, but is actually 20th century in execution.

truss

A roof truss is a framework of timbers designed to bridge the space above a room and to provide support for the roof. Rafters are generally joined to vertical members (eg ashlar pieces and horizontal pieces (eg collars) to form trusses. Trusses usually occur at regular intervals, linked by longitudinal timbers such as purlins.

v

visitation

An official visit of inspection by a bishop or his representative to a church in his diocese.

volute

A spiral scroll placed at each angle of a capital. Of Classical origin, early Norman volutes were quite simple, as in the chancel arch columns at St Michael’s, but became more complex during the 12th century. Those at St Michael’s were probably carved in 1140. The photograph shows a volute capital on the right, and a flat leaf capital to its left.