Inside St Michael’s: the Nave

St Michael’s nave

The present pews, the pulpit, and the tiled floor all contrast with the medieval architecture and the wall paintings to the right of the chancel arch. We are looking at nearly 900 years of history, surrounding you. The Norman church was begun in the early 12th century. The chancel, with its arch, was started about 1140, so we can assume that the Norman church effectively dates from about then. And, as can be clearly seen outside the church, the chancel was later extended, in about 1230. The wall paintings are probably from around 1300.

Go back 600 years and the nave would have looked very different. There would be brightly coloured murals on the walls, stained glass in some windows and images or statues of favourite saints in front of the aisle pillars and around the walls. In 1530, George Rose, bailiff to the Bishop of Chichester, left 4 pence ‘to every light in the church’ — these were candles set up in front of the images to reinforce personal appeals to each saint to intercede on the donor’s behalf. The statues were swept away in the Reformation.

Between the 14th and 19th centuries, no great changes to the church seem to have been made — although, of course, the building had always to be maintained and repaired — and there’s plenty evidence of that in the exterior walls.

North wall of nave

North wall of nave

We are now standing in the south aisle, facing the north wall of the nave with the lower stained glass window and two round-headed 12th century Anglo-Norman windows, their nookshafts with flat-leaf capitals. There’s a quite different window over the pulpit.

The vicar responsible for major 19th century works to the church commented that ‘an unstopped portion of a north door forms an unsightly window, the most judicious treatment of which, and of the circumjacent wall, is a problem commended to ecclesiologists for solution.’ But it was an artist, not an ecclesiologist, who provided this beautiful solution.

We can reasonably assume that the original south wall of the Norman nave, before the aisle was built, would have had a pair of windows complementary to those in the north wall. On the west wall of the nave is another large Anglo-Norman window.

West wall of nave

St Michael’s: west window of nave

You can see the bell ropes in the ringing chamber. So the tower was clearly added later and the previously external west window was left untouched.

You can see how the west window shares its design with the north windows. All these windows are of Caen stone and date from around 1140.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the west window had provided access from the ringing chamber in the tower to a wooden gallery along the west wall of the nave. West galleries came into use in the late 17th century to accomodate musicians and singers during church services. When the musicians played, the congregation would turn to face the gallery. The one in St Michael’s housed the ‘Church Band’ that played until the gallery was removed and a harmonium installed in 1864.

Below the west window is the doorway into the vestry.

West wall of nave

This has a plain, pointed arch. So presumably later than the window above. It would appear that there was no west door originally — no real surprise when the original, north door, wasn’t very far away. So this west doorway must have been created to provide access to and from the tower, when that was built, allowing entry to the church for processions in the Pre-Reformation liturgy.

Chancel arch

Now consider the magnificent chancel arch, one of the outstanding features of this church, and designed to impress. If you stand back in the nave of St Michael’s, or perhaps better still sit in the pews and look at the chancel arch, you will see how it dominates. It is massive, confident. Built to stand forever — and over 900 years later still it stands.

Chancel arch

The zig-zag chevron patterns derive from Saxon artistic traditions. Parallels have been noted with work at Chichester Cathedral but it is now thought that there are closer links with work of around 1140 at Steyning Church. Steyning being only about 10 miles (16 Km) from Amberley, it wouldn’t be surprising for the same craftsmen to have worked on both churches. The arch is essentially all of Caen stone.

Some small pieces of carving of the pillar capitals and several of the lower blocks were reworked in the 19th century. The newer blocks on the curved jambs have clear comb-like marks made by the masons.

You can now get an idea of the scale of this church, which seems remarkably big for a small village — and Amberley has never been larger than it is now. The chancel is as long as the nave — which may appear surprising. It seems likely that since this was the Bishop’s church, he required the nave to be big enough for particular ecclesiastical ceremonies — ceremonies which perhaps would not normally take place in the average parish church. (See footnote)

The position of the arch is not symmetric with respect to the nave. The wall on the left of the arch is much narrower than that on the right. It has been suggested that a side altar could have been positioned beneath the wall paintings. As the paintings end at altar height and the lowest segment is the Crucifixion, this is entirely likely. The suggestion is supported by a 1408 reference (in the register of the then Bishop of Chichester, Bishop Rede) to the “Chantry of Holy Cross in Parish Church of Aumberle”. It seems fairly certain that the south aisle altar was never a chantry implying that the chantry of 1408 must have been elsewhere in the church. So it does appear that the chancel arch asymmetry is due to there having been an altar in the south east of the original early 12th century nave before the 1140 chancel was built.

Votive candle stand

To the right of the painted wall, the wall looks blackened.

Blackened wall area

This appears to indicate the position of a votive candle stand, not unexpectedly adjacent to the side altar – and also close to the south aisle altar.

Pulpit

The Reformation emphasised the importance of the Word of God, so pulpits (and sermons) in churches became a more important element of worship: the reading of God’s word from the Bible became a key part of church ritual. After 1559, in fact, churchwardens were ordered to provide pulpits in all churches. So the earliest pulpit in St Michael’s would probably have dated from mid-16th century. Note the window above the pulpit, which is unlike any of the other windows in the church. On the outside of the church that would appear to be in an odd position, but inside it is clear why it’s there: to provide light at the pulpit. So that window will date from when the first pulpit was installed.

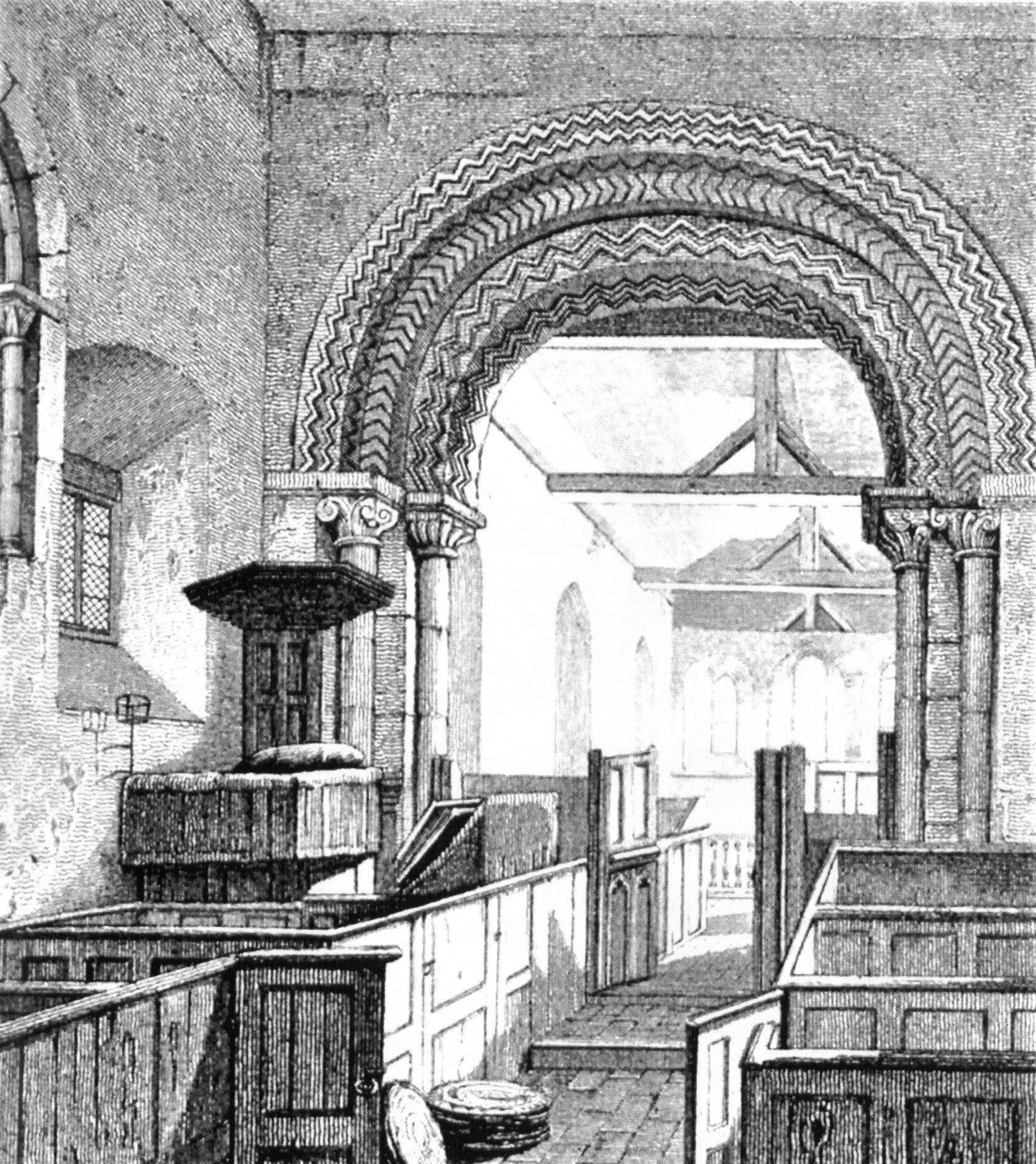

The current pulpit was installed in 1909 and was preceded by at least two previous ones, one being installed in 1865. The 1820 engraving here shows a pulpit which appears to date from the mid-17th century, so there may have been an earlier one.

St Michael’s Church interior, 1820 engraving

Note the metal bracket on the wall below the pulpit window. This is an hour-glass stand. Hour-glasses were introduced in the 16th century and became usual in the 17th, to time sermons. Some preachers would invert the glass when the sand ran out and continue their sermons. The one at Amberley, which was decorated with cherub heads, was stolen in 1970.

Amberley Church hour-glass

Early seating in English village churches would have been benches but box pews were installed in the late 17th and 18th centuries. (You can see real box pews at St Michael’s sister church at Parham.)

19th century reparations

In the nineteenth century, ‘restorers’ made great changes to many English churches — much to their detriment in many cases. St Michael’s was no exception. In 1864-65 over £100,000 in today’s money was spent on major works to the church. The old box-pews were removed and the current, pitch-pine, pews installed; the west wall gallery was removed; a new pulpit was installed; the stone slab floor was replaced by coloured Minton tiles. Much wall plaster was removed — we’re lucky that so much of the wall painting is still there. There were major repairs to the external walls and to the roof, which will be discussed when we consider the exterior.

The old pews apparently went to various local farms as pig troughs and the old flagstones went to pave various barns, etc, in the village. All the inscribed stones were supposedly placed in the porch, but there’s only one recognisable.

In the 1820 engraving above you can see that there was a gate between the nave and the chancel, which was removed during the 1864 ‘reparations’. In medieval times, the chancel was reserved for the priest and the nave for the congregation. There would be a screen between the nave and the chancel, with a locked door to keep out people and dogs. Over the screen would be a Rood beam, on which would be fixed a Rood — the image of Christ on the Cross, flanked by the figures of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John. St Michael’s would certainly have had a Rood screen, which would have come down in the reign of Edward VI (who reigned from 1547 to 1553), been re-erected during Catholic Mary I’s reign, then taken down again after the accession of Elizabeth I. The low screen shown in the 1820 engraving would probably have been from the time of Archbishop Laud, after 1630.

While many screens were erected in front of chancel arches, others were placed within the arch. So although the chancel gate was within the arch in the early 19th century, this does not mean that that was where the original rood screen was placed. However, nail holes in the chancel arch jamb shafts suggest that the screen was within the arch.

Footnote

It has been suggested (by the architect P M Johnston) that the ‘priesting of ordinands’ en masse by the bishop is the reason for the apparently excessive length of the Amberley chancel compared to the nave — especially since the priests had to lie prone during the ceremony. But it is not really necessary to adduce this reason. For in 1215, the doctrine of transubstantiation required clergy to ensure that the Blessed Sacrament was kept protected from irreverent access or abuse, and the nave became screened off from the chancel. This meant that the chancel had to be of adequate size for ecclesiastical ritual. The consequence was that the vast majority of English chancels were enlarged in the 13th century, with many doubling or even trebling their floor area. So there is nothing unusual about the length of the chancel here.